Dr. Aleny Couto, recently named one of Newsweek’s “Women of the Future”, has spent the last six years leading efforts to curb Mozambique’s HIV/AIDS epidemic. As director of STI and HIV/AIDS Programs at the Mozambique Ministry of Health, Dr. Couto is in charge of designing public health policies and strategies to attain HIV epidemic control. According to Dr. Couto, differentiated service delivery (DSD) is an important part of addressing the epidemic in a country where HIV/AIDS affects roughly 13 percent of the population.

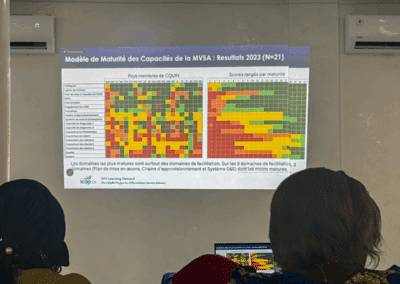

Last year, at the CQUIN launch meeting in Durban, we spoke to her about the big questions surrounding DSD. We caught up with Dr. Couto again at our annual meeting to learn how CQUIN has shed some light on those questions, and contributed to DSD scale-up in Mozambique.

Why is DSD important for Mozambique?

We’re about to have one million patients on treatment here in Mozambique. Most of our health facilities are not prepared for this, so it’s important that we come up with innovations to care for our patients and health workers. As patients become healthy, it’s important they feel things are getting easier for them, not more complicated. Patients often cite fear of stigma and discrimination and long queues at clinics as barriers to care. Differentiated service delivery is one of the solutions that we can integrate into our system to help deal with those issues. Formalizing these models, most of which were already in place but weren’t called DSD, is important for reassuring patients and providers that this can change things for the better.

What are some of the unique challenges to scaling up DSD in Mozambique that may be different from those of other countries in sub-Saharan Africa?

Having uptake from providers can be a challenge. Community adherence support groups were proven to improve retention, but getting a commitment from the providers can take time. It’s important that we prepare and have good communication strategies so we can reassure providers that this is important. Demand creation for DSD from patients is another thing we must work on if we’re going to scale-up differentiated services.

Mozambique is a very big country with a variety of cultures and customs. Some things that work in the rural areas or in a community setting may not work in Maputo City. Preferences change by region, so it’s important for us to try different solutions.

Have the priorities for Mozambique changed since we spoke last year when the network began?

The key thing that really changed is that we’re going to start distributing ARVs in the communities, and we’re using systems that are already in place—like mobile brigades—that were used to provide vaccinations and mother-to-child services. Having a group of countries that we can go to for support that are doing similar things is helpful. If we see something is working elsewhere, we have evidence and can push for those things here. We’re still developing our guidance, but there are already some DSD models in place, like community adherence support groups, fast-track refills, and three-month drug distribution.

You spoke about the importance of demand creation. Last year, you said that patients and providers need to understand the models and the concept of DSD. Do you think there’s been progress on how providers and patients understand DSD or demand for services?

We haven’t seen much improvement, and I think it’s because there needs to be investment in communication. As a network, we should discuss how to improve communication materials and demand creation. We discuss the models, but how do we improve these models with tools that will move patients to demand services? We need investment from donors. Donors want evidence. We need to get that initial evidence.

Communicating DSD to patients and providers needs to be part of the overall package. That would help us kill two birds with one stone. It would be much easier to bring all of these pieces together into one package on DSD, instead of negotiating each thing individually.

What are Mozambique’s DSD plans for the coming year?

We have many concerns about distributing ART in the community, and I want to see if these models are going to improve retention. If it works, we need to consolidate. That means we can start evaluating the DSD that’s already in place with CQUIN. Qualitative studies are also important. We need to think about psychosocial support and the social part of being a patient, because being retained doesn’t mean that you adherent to the treatment.

This story is part of a series focused on the evolution of the CQUIN network, and countries’ progress in improving differentiated service delivery. To follow this story and others, sign up for the network’s monthly newsletter.