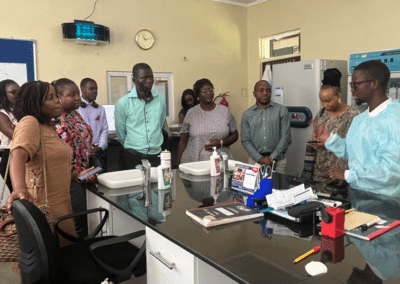

Satvinder (Vindi) Singh is a medical officer who leads TB/HIV and quality of care within the HIV Department at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. Dr. Singh was a member of the planning group for the recent CQUIN workshop on differentiated service delivery (DSD) for TB/HIV, co-convened by ICAP at Columbia and WHO from March 26-29 in Lusaka, Zambia.

Dr. Singh reflected on the recent CQUIN and WHO meeting on DSD for TB/HIV services, noting that in order to meet targets, and eventually end the HIV epidemic, differentiated HIV services need to address TB prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. She noted that approaches must be carefully considered depending on context and patient needs.

What is your background and why is DSD so important for TB/HIV services?

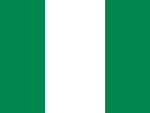

I’m originally an HIV clinician and family physician. I managed HIV programs at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Nigeria, Rwanda, and South Africa before I moved to WHO as medical officer in the HIV Department, where I’ve been for almost four years.

Tuberculosis is the biggest killer of people living with HIV, causing a third of HIV deaths in 2017. We have a major ten-year target approaching in 2020 to reduce TB deaths among people living with HIV by 75 percent. In 2017, they had only decreased by 42 percent, so we still have a long way to go.

Screening and diagnosis of TB amongst people living with HIV is a major challenge. In 2017, we estimated that there were 920,000 cases of HIV and TB co-infection, but only half of them were notified to TB programs. We also have a big gap in antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage for co-infected people. Fifty-nine percent of the 37 million people living with HIV globally are on treatment, but of the those co-infected with TB, only 41 percent are on treatment, which means we’re missing the sickest recipients of care who have a high risk of mortality.

DSD is the way of the future for HIV services, and we need to ensure that we’re getting people started on TB preventive treatment, diagnosing TB promptly, and linking them to effective treatment within these models of care. It’s also important that they have quality care, achieve good outcomes, and are virologically suppressed. Differentiated services can help patients stay in care and get the right treatment in a convenient way.

Is it feasible to integrate TB/HIV services into differentiated HIV treatment models?

Yes. If a person comes into the clinic every three months to pick up ARVs, it’s important that they are assessed for TB and educated about TB symptoms. Part of the DSD approach is having the right education, peer support, and other wraparound services so people on ART know to come to a health facility or contact a health worker if they have symptoms that could indicate TB infection.

We’ve also been discussing TB preventive treatment (TPT), and the fact that many countries are falling short of their coverage targets. While we heard at the meeting that some HIV programs focus only on providing TPT to people newly diagnosed with HIV, per WHO guidance, all people living with HIV are eligible for TPT unless they have previously received it or are otherwise ineligible. Thus, TPT can and should be offered to stable recipients of care in DSD models. DSD models are variable in terms of how often people on ART come to health facilities, so we’d have to tailor TPT approaches accordingly.

What are the unique challenges associated with DSD for TB/HIV?

One of the issues related to providing TPT to people in DSD models is that they come to health facilities less frequently than patients just starting ART. At the moment, most countries use isoniazid (INH) for at least six months for TPT, and most are accustomed to monitoring recipients of care on INH monthly. So, there are interesting questions about how to handle this for people in DSD models, and whether monthly monitoring at health facilities is necessary. These issues may be easier to handle when countries switch to newer, shorter TPT regimens.

The other challenge is ensuring that individuals are screened for TB between clinical encounters, as these become less and less frequent for people in DSD. With the right education, a TB diagnosis is less likely to be missed because recipients of care have been given the right knowledge and responsibility to self-identify. Many individuals don’t want to be diagnosed with TB for fear of stigma, but if we empower them and provide options for support or group counseling as part of a community adherence group (CAG), they may accept there’s a benefit to being diagnosed early and getting treated.

What are yours and WHO’s next steps following this meeting?

The CQUIN meeting was a great opportunity to discuss these issues with a diverse audience. There were many questions around the global guidelines, shorter TPT regimens such as 3HP (3 months of weekly INH and rifapentine), including interactions with dolutegravir, monitoring of TPT, and recommended frequency of TB screening. I’ll take those questions and concerns back with me as we develop future guidelines. We’ll also have implementation guidance that will come out later this year and some of those questions can be answered in that context as well.

How do you think CQUIN can help countries integrate DSD and TB/HIV services?

As a learning network, CQUIN provides multiple opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, including the exchange of very practical lessons and tools. It would be great to have webinars and a virtual community of practice around this specific issue. There’s a lot of opportunities to exchange information and make TB/HIV services a priority for countries moving forward.

View the TB/HIV meeting summary